What emerged

We all convened on the SAIKS seminar room at 10 am on the Saturday morning waiting for John with the key. Most people already knew each other and we caught up on the latest state of affairs in all our lives and introduced the newcomers. Before long we were all inside and had put the food and tea and coffee on the table and set up the whiteboard, and the video camera.

Michael gave a welcome and talked about what we were here for, and some of the business to do with travel, payment, and accommodation.

Before long Frank told Michael not to talk too much. If you go on for too long we’ll forget and go to sleep, its’ better for the questions to go back and forward.

Michael pleaded, just five more minutes of me talking then open to you guys. He wanted to talk about the methodology, how do we go about doing the research, looking at balanda and Yolŋu ways of making knowledge. He referred to the metaphor of garma, coming together, exchanging views, building agreement, trying to find as many different ways as possible, so we can come out with a lot of different ways to get the solution. How do we make knowledge? Storytelling, discussion, writing, Yolŋu matha or English, talking on video, diagrams, spaces and places, inside and outside the seminar room, freedom to come and go, paper for drawing, white board. Michael said that he hoped that by tomorrow afternoon some sort of shape about what we’ve come up with will emerge. He would do notes on the computer, and there was money to make a website to represent our ‘findings’.

Then it was suggested that, since there were a few people who didn’t know each other, we should all formally introduce ourselves. (Short introductions can be found in the About section)

After the introductions Maratja set the ball rolling with a comment about Yolŋu language in Yolŋu schools. His first points were that Yolŋu language is a key entry point into Yolŋu education. It is very helpful for the children’s understandings, for ideas, concepts, and the Yolŋu world view. It is also useful for understanding the balanda world view, but also people have to take pride in what of their own they are learning. He introduced the word miŋurrmirr, and interpreted it as value.

What do we value in education? He continued; the current education system is only the balanda way of doing things, balanda way of maths all the time, value has been placed through the balanda way, but what about the Yolŋu way and valuing the Yolŋu understanding of world view, where are they?

Where do they meet each other, (dhol-bunanhamirri) and where do the differences lie? We need to understand the two extremes, and make some balance.

Maratja made clear that he was here to learn about the different systems, so he can go back to Elcho and help with the education in the school. Why are so many children dropouts? Why can’t they even see maths properly? Where are we going to help our own Yolŋu children, so they become good achievers? Where does the value lie? In whose world? The balanda world view, or the Yolŋu world view? Is there a difference between the two? How do Yolŋu view maths, how do balanda see maths? Where do they come together and help each other?

Michael suggested that we should note some of the key concepts which come out of the discussion, like miŋurrmirr. Looking at key concepts might be a good way to look at connections and disconnections between Yolŋu and balanda worlds.

Rose the interpreter said she was still unsure about what we were working on. Are we making a report on how Yolŋu language deals with balanda mathematics, is that what they want to know?

Michael said people could talk about whatever they thought was important, but he thought the important point was not so much about Yolŋu language for Balanda numbers, but how numbers, like cars, or money, come into a Yolŋu community and get taken up for Yolŋu life. How do numbers find a life in a Yolŋu community?

Frank posed the question: When a balanda says our attendance is 45 percent, does that have an equivalent in Yolŋu language? What does it mean? Maybe to us it’s lurrkun’, but lurrkun’ also means ‘three’. When we say lurrkun, do we see that as a percentage or what?

Then he mentioned that outside they had been talking with Waymamba about ‘shapes and sizes’ and the ceremonial way of dividing up sacred bread made from cycads. The old people used to use that word yony-barrtjun referring to dividing up each loaf. It’s a strange word for balanda maths, there may be an English word for it.

Frank went on to talk about how, watching the tv, he has no idea what they are talking about when they mention stocks and shares and commodities and fuel prices. And balanda have no idea about what Yolŋu are talking about. It’s hard to know where to start this ‘brainstorming’.

Dhaŋgal then spoke up with an example of ancestral song. Let’s forget about balanda maths for a moment and concentrate on the Yolŋu side. Whatever Yolŋu do in their culture, there is maths in it. For example ancestral song, that’s talking about what English maths calls distance. If there are patterns underlying it, there has to be something in English that’s similar, in our designs, the waters tell it, the kinship tells it. In all these there’s maths included in it. That’s how we see it, with our djalkiri, that’s where it comes from."

Then Wulumdhuna stood up and took hold of the young four year old. What’s this boy’s name? He is my gaminyarr, and his name is Djunuŋgu and do you know that name Djunuŋgu? Write it up on the whiteboard and then I’ll tell you. It’s from song, from gayku, Wanama`.

Waymamba talked about the differences, in names and other things, between how Yolŋu use names, and how the Balanda use those names in their maths. We Yolŋu understand our own patterns and whatever, and balanda try to teach us their idea of how they do maths. They’ve been doing it for a long time, but we still don’t quite recognise their way. Just going back to the kids in schools, they find it very difficult to do school maths. That idea is very different from Yolŋu philosophy, inside the head here, (pointing to her own head), these Yolŋu heads are very different from Balanda, we don’t recognise each other, we don’t understand each other.

Frank suggested we wind the clock back: I want to ask a question because some of us went to the mission school. Did we learn? Yes I think we did, but not enough in the mission school. How is my education different from the ones they get at school today? It’s a hypothetical question.

Dhaŋgal suggested a key difference; that schooling in the mission days used to involve the community, encouragement, mothers and fathers, but these days there’s too many distractions, all sorts of different things are coming along, and the kids are distracted by them.

Frank agreed that the effect of “outside influences” was an important answer to his question.

Gurraŋgurraŋ who teaches in the remote independent homeland school at Gawa on the top of Elcho Island, then spoke up about the kids in her community. I see the kids, the ones we are growing up at Gawa, they know maths, they understand, I took them off their mothers, and taught them last year and now they are adding up by themselves, they understand how maths works, teaching them maths and English. So when they are seven, eight or nine, there’s no worries for them. They learn really well, that’s what I want to say. When learning about kilometres we did the numbers along the road, the Gawa kids, from Galiwin’ku to Gawa. Every day we work outside, and inside the school, and those kids, from three to seven, they add up all by themselves. If I teach those kids like that, they will know when they grow up. And it will be easy for them when they are older to learn about other things when they grow up.

Wulumdhuna, the Assistant Teacher in Charge from Djurranalpi homeland centre school told of how when she’s been teaching the kids from year one until they are year six, it is all good, but then by the time they’re year seven it starts getting difficult, gumurr-dalthina. So I go back and teach through cultural understandings, lukukurr, back there, locating through the environment. One example: that kid I pointed out, he is named from a type of cloud, gayku, and we see that over there all the different places that cloud goes to, it talks about the connections through which we recognise each other. Many of the kids are struggling there in the big school, (at Shepherdson College at Galiwin’ku). It’s hard there, in what they are calling the middle school, that’s when they find it hard. They need to find where we Yolŋu have ancestral connections, in their own place where their feet (luku) claim identity, (balyunmirr) then they can go on to make connections with whatever places, just as if that cloud will take them. First they need to understand the Yolŋu side, then if they go back, they will understand the balanda side.

Gotha, the senior custodian of Gawa community and teacher of 40 years experience, then spoke up. We look at the water, when the tide will be out, there’s maths in there. How the tide comes in, and goes out. When the moon will rise, the kids learn. When the moon dies and the new moon comes along. When will it be full, there’s maths inside there, and in the seasons and the clouds, they know these things and their land, and the Yolŋu caretakers who stay there.

When kids don’t have their own land, (because they are living in towns) there are many things in the towns to distract, and negatively influence (baduwaduyunamirr rom) the kids. There isn’t one child in the towns with the focus to learn. They don’t have settled heads for learning. But at Gawa we are living together and at the neighbouring homelands at Naŋinyburra, Ban’thula, and Djurranalpi, we are learning by ourselves. When the wind blows, when it stops, when the mosquitos start, those things the land is teaching us, on the maths side, and the kids keep on learning. When the children go to school they learn because they have this knowledge.

Gapany, who taught at Shepherdson College, Galiwin’ku for over a decade talked about the environmental Yolŋu maths knowledge in the community. The season right now is called midawarr, so lots of people are taking their children hunting. Those kids know all about fishing, to go at full tide, when the tide comes in, they go, and when it goes out they collect mirriya (bait crabs), and know when to go back fishing again, see it’s midawarr time now. They know about which tide and which moon, and which tide to go collecting diyamu (sp. shellfish). And the kids will say. Come on, let’s go hunting for fish. They say: What’s the time? What’s the tide doing? Who’s going to check if the tide is coming in or out? If it’s the wrong time, we’ll do something else, go into the bush or the mangroves for crabs and when the tide comes in we’ll go fishing and catch lots of fish. That’s what this midawarr season is like.

This is the first time for me to attend such a workshop. Even though I have been working in the school, team teaching maths with Yolŋu and balanda. But for Yolŋu way of seeing, I learnt more through hunting, and working around the home. Like with the girls, it’s good, like the scoop for the Rinso, just use one scoop, not two or three, it’s too much, it’s that experience. Go and wash five cups, waŋgany rulu, waŋgany goŋ washim, those sorts of things at home, real life experience, that’s what I find at home, and counting shoes, whose is missing? Once they get into the habit of learning, two shoes, where’s my pair? Washing two plates, that sort of thing, once they get home they do it for themselves. First I thought that these things were not maths, but as I was thinking of Michael’s introduction, although he did talk too fast, and some of it went over my head, it brought me back, to what I missed out, and made me think of what I’ve missed out on teaching the kids at school.

WG: there is a pattern of maths on the Yolŋu side, the language of maths on our side

Frank: I’ll just say this in language, I was listening and it’s true what you said, that in our home there is maths in whatever experience we’ve had before, for example I learnt maths at school rather badly, if I had been smart, my maths would have been about seven if you work it out (on a scale) between one and 10, seven maybe six at school, and, when I left school, and was working and after hearing about the experience, working and living in Yolŋu communities you learn more, which you can take through the paths of Yolŋu life (you need to interpret for me because we have two interpreters here), like turning the knowledge around and taking it back into school, I learnt more by going back home and I learnt at home, through our own law, mathematics, when I look at this maths (discussion), it really opens up why that happens, and then I can match them up, some people say that there’s no match? Between Yolŋu and ŋapaki mathematics. you can correct me if you like, But in some way they do, if you see how the Yolŋu understanding sits, and then you find how the balanda system goes, they will both work. If you marry them together you might get some understanding. That’s what I’ve been hearing, that’s where we get understanding, we need to go back, to where we received the foundations, to kinship, the moon, seasons, those sorts of things...

JG. How you see the world...

Gotha: talking about two different sorts of turtle one is dhalwatpu and one is birŋarr, you need to look at the tracks, and anyone who doesn’t understand will be digging in the wrong place, if he can find it easily, he has a good eye, so he can dig them up straight away, like now even Colin (her balanda husband) knows how to find them, but the dhalwatpu will put false nests in, maybe four five or six. And if he doesn’t know it’s there, there is a secret lying there, and if we don’t know there is a secret there in his tracks we should learn it, and also if the balanda gives us something then he might find something to learn himself. If it’s that sort of turtle, he’ll search here or here or there, and you will find false nests, he might be digging all day... If you sit down and study it, and find it...

Discussion and laughter

John: the one who doesn’t understand, how will he learn? (pointing to the whiteboard) learning at home, talking about the different turtle species and how hard their eggs are to find. How will a balanda or a Yolŋu learn?

Gotha: they’re both the same (balanda and Yolŋu)

JG: How will they learn?

WG: From a knowledgeable Yolŋu. From following the words of a clever Yolŋu.

JG Do you learn here (school) the same as at home?

Yes,

Gotha: They are both helpful. If he learns at home he will understand and take it to school.

Maratja: Balanda should teach using metaphors, pictures, use everyday examples, comparing contrasting, telling the story, give it meaning by referring back to real life experiences, (these experiences) will tell the children, like when they ask, how is that so, like there, there, there, that’s what Yolŋu are thinking, just like looking at a picture, that’s its meaning, what is its length, where to cut it, a spear, or this food, talking about warraga (cycad) bread, that’s good, all Yolŋu have experienced, through practical, old people, women, some of this food is for wana-lupthunamirr times, and also for ceremonies, through political and cultural areas, how to dividing the yony, buku-bakmaranhawuy loaves, what is means, how to make the bread, who has made it, when to share it, who to consider when sharing, relatives (gurrutumirr), thinking of ancestral connections (reŋgitj) and clans (bapurru), or if only he will eat it, later during ceremonials, cut the bread in the right way, so all the connected clans can taste the right way, ceremonial managers (djuŋgaya, yothu), everyone, there are ways, protocols, not just anyone can partake, there are ways (rom).

MC how does this compare with the classroom

Frank: I was speaking about my experience, so correct me if I’m wrong, when I look at maths, (I’ll talk simply) when I was learning about multiplying and dividing when I was working, when I went back you can do the same thing at home, dividing up and sorting eggs, dividing turtle, it’s “exactly the same” sort of mathematics, that are use at school, like the beads on string, counting, calculating whatever, but when you turn it around from doing it at home, counting or whatever, when you go to school you might be using beads or something they will both come together or be equal (rrambaŋithirri) and your maths will be very good. For example percentages, you might have a rough idea or an exact idea, what percentage might it be? Ten percent?, fifteen percent, percentages are lying there with Yolŋu, how to tell that they are there, lurrkun, marr gaŋga gandarr there are different words there for that… if I can do counting at home, anything, maybe tracks, nests, laying eggs, different things tide in out, that’s a way of telling, later when you get to school the teacher says, ‘Here you count this’, ‘you tally it up’, bothurru nhamunha’ dhuwal, they’d think ‘Oh yes, that’s like the work I do at home’, makes it lots easier, that’s how I found it. If you don’t know Yolŋu bothurru you will find the balanda maths side of it very very hard. Even if you can count in English at home, still a Yolŋu will dhumbal’yurr (confused, confounded) unless you can count in Yolŋu first, that’s my experience, the others may have had a different experience...

Maratja: I think that world view, Balanda maths it’s a world of its own, separate (barrkuwatj) from which we are alienated, there’s nothing in there to which we find connection, we are disorientated, there is no connection, we must learn why, the rationale, find the reason to learn, you are learning these things for this and this reason, so that you will feel comfortable confident (marrmirriyirr, ŋayaŋumirriyirr), and understand (dharaŋan), so that you can help your relatives, because old people are there, make sure you that your work is good, “fulfilling the task” properly, not shoddily, if you do a bad job, you will go back and there will be trouble, you go the right way.

Frank: ….Yes, Bulany (John) and mit (Michael), sorry I interrupted. Mango, yeah mangoes, we find them out of season. We don’t eat cycad in the wrong season… we go into the shops and we see all the mangos out of season… if there was a Yolŋu shop and we would see warraga (cycad) out of season we would know that it was wrong we’d know how to find it.

Rose: Yes, we know from the thunder, when the first wet season comes, we see the thunder clouds and hear the rumbling, male and female, and we become ready, we’re ready for it for the cycads. There’s one thing, the wattle tree, yellow, when the leaves are green, it’s not the season for turtle hunting, but when it blossoms yellow, it comes out, it tells us it is the right time to go hunting turtle, it’s the right season. That’s an example of how when we look at plants… I was just listening, what we were talking, I’ll just ask a question, I saw a similarity there, it’s a bit like talking about finding from Yolŋu rom, how it is that Yolŋu learn, from both the Yolŋu ancestral side (ŋurrŋgitj), and on the balanda side, there is a connection there, already there, similarities are lying there, but all different colours of Indigenous people struggling on, and we find within the community each community we will find complications with the education, both Yolŋu education and balanda education, I’m not sure if I clearly understand this, but I find them both hard, and our Yolŋu thinking it’s best if our children learn in Yolŋu ways first, in the ways in which we raise our own Indigenous children, before we come in to be learning balanda matha, English. There are two ways which they can learn with manners-mirri (respectfully), both Balanda and Yolŋu ways can be done with respect, so I was thinking is that true? Sometimes we find it very hard because lots of our children get carried away looking at other things, something looks good in their eyes, and they get carried away forgetting their cultural background. Can’t spend more time with the parents or ŋathi or mari’mu (mother’s father and father’s father) and it becomes hard for them to come to us at school and learn. It becomes a big problem for some kids. Am I right?

WG How do Yolŋu find the patterns of language in every day life? That’s what we were talking about, and now Michael has asked a question: What does it mean those things, to their place in a school? How do these things take a place in a balanda (European) school, and how will we do that? That’s what Michael asked.

Maratja: Hard question, truly a hard question...

General talk...

Maratja: Maratja signals that he wants to talk. I’m here to find a way, “how can we connect, can we improve the standards of our education system, particularly in the maths area, in schools in Aboriginal communities right across, where does the system work, because the systems are crossing each other without meeting (djulkmaranhamirr), not recognising each other Yolŋu (and balanda). How do we give our children a good system? Particularly with maths.

How will our maths enter (garri) into the curriculum? Now it's your, a struggle for you teachers, to try and convince the government, and NT education system and department to recognise this (rom), some will not understand, some would even scrap Yolŋu matha altogether, we won't go backwards to those times, they think there is only one way, and “(yolŋu) should try to become like us.” “Learn this! learn that! learn our (balanda) maths and what ever else.” Lots of us have maths we ended up going to high school, and lots of didn't understand and didn't end up pilots, doctors, and other professional worker. There is a way (rom) to recognise each other possibility (djinaga), these foundations by which we can understand each other, needs unravelling, straightening up (dhunupakum), dhunupamirriyam, so that somehow a way for us to recognise each other, connecting to here, like this, If it is to grow, then there needs support foundations for later, the kids will learn truly, then they’ll go through, get a good education, what it (school teachings) means from the younger maths to the very big ones, like the scientist going to the moon, probabilities and possibilities. that space is different, there it is very hard, for us Yolŋu maybe we see things crookedly (djarrpi?), lacking (yaka gana’), or we see ourselves as (djarrpi?), how can we connect, how can we try to understand if we were to go only one way, conformity for their law, to only their standard and structure, if we follow their structure we will end up going to some undefined place, we don’t know, at the moment, down south, in those places the water is drying up, global warming taking place. Most of the trees have been cut down causing no rainfall, the scientists are telling us, according to space and mathematics and conformity, you end up abusing your home/land, no water, no rainfall, drought happening, our Yolŋu way is one of respect, not abuse, take a little bit, what comes through the seasons of your culture, is that maths, or what is it? Our world view.

WG it’s like this waku marrkap, when we were kids learning, at the time that the Yolŋu (teachers) took over (from the missionaries), what are the kids learning today not in the homelands, but in the town schools, the community schools, are they still learning cultural activities?

Gotha: Yes at Shepherdson College

Gapany: Well, these days I think it’s me being frightened to teach maths, he knows the balanda ways, the names, and I am a Yolŋu and I learnt my own knowledge and I fear teaching because I don’t understand how can I make a contribution to their knowledge? I need to understand, those points (gamurru) I have to teach, my fear is in maths, at teaching

MC afraid?

Gap: Yes afraid that I will (bawa-gurrupan) give the kids confusion, if I don’t know. And my experience, now that I’m getting older, is that I’m learning more about Yolŋu maths, from Yolŋu words, from real experience, going hunting, talking to Yolŋu older people, sharing with mother uncle, and friends, going together, hunting and seeing shellfish fish, that’s the knowledge, getting it while collecting that information and teaching to kids at home, it’s how language Yolŋu language and English, we know a Yolŋu language in maths, we know the balanda language is different, totally different , we know the Yolŋu language of maths, balanda totally different pattern, space, time, location, different. Ours we already know it, and we sit it, and sleep it, everyday life, we do that everyday life. .

Maratja: And when we know that way, we don’t ask questions too much, balanda they are always encouraging asking questions. We don’t ask those question because of that fear we grow up like that, (pointing back to his wife who has just spoken about her fear teaching)… If there are too many questions we see ourselves as being a bit cut off, we see ourselves as like a rude Yolŋu asking to many questions. That’s how we feel insides ourselves.

Gap: Like who is the expert? They talk about experts, who’s the experts on that thing, if it’s to do with balanda, we ask the balanda expert, if it’s on the Yolŋu side, we ask the Yolŋu expert.

M: … and how can Yolŋu and balanda work together on bilingual education, if the balanda teachers are not trying their best to learn Yolŋu matha (language)?

Gap: They don’t learn to speak Yolŋu matha,

M: How can they teach if they don’t know some of the cultural significance? That’s where the big gap lies between balanda and Yolŋu

WG: that is the next point, we will put in our Yolŋu laws/ways (rom) so they will learn, for the whole community

Gap: Recently the community was invited by the secondary school, we have a new principal at Galiwin’ku, and many kids are heading into Darwin schools, I known those kids when they were younger at school, same like my son Wamut, and also younger ones, now I am very worried, and I am a community member, parent, grandmother, to the school, for the secondary school, there’s no Yolŋu matha, they give them different issues, study are very good, but I am very worried about the reading and writing Yolŋu language,

KG: Where Gapany?

Gap: These are old children, there recently, , when the new principal arrived, on Friday we took the whole day, community parents and secondary school, recently at Galiwin’ku, that was culture week for them, from Tuesday to Thursday, the Dhuwa in one group and the Yirritja in another, like that, when I to the secondary meeting, we were sharing, we from all the community work departments invited all the people, where they are at, what work they had and what they were doing now, are these people the leaders for tomorrow? Or those other ones, question like that, … make them think how they will become better people, don’t carry a child early, don’t smoke marijuana, don’t drink, don’t go night prowl, wandering streets every night. That’s how.

M It’s one thing to give them raypirri (discipline) but you also need to give them options,

G I’m talking about kids not adults,

M Take them hunting so they can learn about Yolŋu time and space and meaning. We need to give them opportunities, so they learn, some of them are rebellious, in our community

G: So we have two senior men, Buthimaŋ and Gaki, teaching (community elders) older men who are there to help out. They give a lot for the children’s learning, how they had learnt themselves, on the balanda side and the Yolŋu side, and the balanda culture, how to recognise, how to go into balanda culture, … and if you know the law of God he will help you to enter into both of them properly… taking things much further (like you were saying very quickly this morning) something that’s important to you, Yolŋu maths in everyday life, and that’s where I sit, and I have learnt a lot from her, from her (pointing to Gotha)

Gotha: When did you learn from me?

G: At hunting, I learnt from you, ‘Let’s go here and find this selfish’, ‘Now is the right moon for this’… didn’t you notice?

M: when the tide goes right out a long way, what’s that, our tide story, when the tide is right out, the moon tells us,

RL: when it’s noŋgurr (new moon), the water might be good or bad, and then it might bring lots of fish in the river or the billabong, and when the full moon comes out, go for turtle. One moon tells you that the tide will come in only a little way and then it will go back again, and the full moon comes, and the tide will go right high,

M: same, some of us are not teaching our kids, they are not learning,

JG: where do the different clans and moieties separate out – this one is Dhuwa this one Yirritja,

Gotha: waŋganyŋur (together)

Discussion,

Gap: it’s the reŋgitj (totemic words and places), that tells you (where the different groups separate). They each have quite separate reŋgitj. You (balanda) just call it turtle, whether it’s green or what it is,

M; (joking) No, that green one belongs to us (dhuwa people)

Gap (his wife) no, no I was just saying, it’s the reŋgitj which tells you the difference.

Laughter..

MC to JG: Waku (nephew) is there some food here somewhere?

F: let’s take a break

MC: Yes, and people might want to talk or Kathy or Christian or Anthea might want to ask you questions, so well take a break and get back after a cup of tea...

Gotha agreed and added that at Gawa the children find it easier at school when they have good understandings of Yolŋu environmental maths and because they attend school every day. It is important not to add new ideas that make them think in boxes. Let the children learn by experimenting. At Gawa, school, home and community work together. She gave the example of her six year old grandchild who is actually quite naughty, who walks in and out of school, but is living happily on his land with his family, and he’s learning his Yolŋu reading well, and later he’ll be quite ready and able to learn balanda maths.

Wulumdhuna added how she was often surprised to hear kids performing their own songs and dance buŋgul, and getting the concepts and processes and words or ancestral ceremonies right. She wonders, where they pick up that difficult adult knowledge?

Maratja turned the discussion back to his own schooling. They taught us about numbers, tables, times, additions, subtraction, learning about all that. It took a while to learn all that, it was hard, it was repetition, we used to go from simple to quite hard, like high school maths, but there wasn’t any connection to our environment, to help us understand, it was a vague, like from a different world. No contextualising with our everyday life experiences. There has to be a reason, a rationale, a purpose, so we use it for a practical purpose like working in a bank. The parents heard the story and tried to encourage the kids to learn maths, to work at the bank or somewhere. Some we could understand, some we couldn’t, but there was no grounding, or good foundation. It was not breaking through to us, for us to recognise and understand that maths, such as levels 3, 4, 5. They were too hard, it caused us to fail. I was working as a fitter, motor mechanic, and in my second year I failed electricity. They wanted me to go back and do it again, I failed, it went over my head, it wasn’t clicking, and I couldn’t understand it, so I decided to give it up. There was no ground work, we didn’t have the preparation or foundations.

Bryce suggested that if you don’t really understand how the base ten works, you can’t work all the formulae, if you haven’t learnt really well about going from 1 to 10, 10 to 20, the way we use maths we can’t understand formulas because underneath them we have the information in the equals sign.

Maratja commented that a formula is some thing which can be taught. What is a formula? What does that mean? Maratja is a translator and interpreter, and confident he could teach Yolŋu so they could understand what a formula is, using some examples from Yolŋu culture to explain formulae.

John talked about the formula for voltage and resistance, and wrote the formula VtIR on the whiteboard. There are ways of talking about electrical flows, like using the example of the waterfall, the height and volume of water flowing. John then drew a few different variations of diamond shapes which Yirritja clans use to differentiate themselves, on the whiteboard.

Bryce submitted that the notion of equals is bizarre, it doesn’t make sense outside of base ten. If V is said to equal I R, that requires base 10.

There was some disagreement about that.

Michael suggested there may be equivalents to ‘equals’ in Yolŋu maths. For in kinship terminology, does a waku’s waku equals a gutharra (a daughter’s daughter equal a grand-daughter?)

Maratja: Science is encoding information, like how many Yolŋu here know the messages encoded in a message stick? Nowadays maybe only the old people know.

Maratja, reflected on the maths in his apprenticeship training. If I had some, measuring, some foundations, detailed explanations, (maŋutji-lakaram), some Yolŋu there with me, telling me stories, some mentors with me, explaining to me in Yolŋu language (matha) the meanings, how it works, and the contexts, concepts, comparing the Yolŋu ideas, the relevancy of it, the appropriateness of it, using those techniques, going back to where I had missed some of the foundational stuff in the mathematics. I could have gone a long way. It would have made a difference. That’s how I think, I could have acquired the knowledge.

In terms of the apprenticeship, I don’t have any interest at the moment, but if other people were to have a bash at it, and at understanding some of the concepts, I would be there to tease out some of the areas which need to be grounded, to help them through that alienation.

It was now nearly four o’clock so Michael tried to sum up what had come out of the day. Two things, the use of Yolŋu maths and language in the classroom, and balanda and Yolŋu maths in the Yolŋu community. If we can bring them in at base level how do we keep contextualising the work the kids are doing in the classroom? It seems the kids need a firm background and maybe we’re trying to do balanda maths too early?

Maratja said that bilingual education helped to keep these contexts going, but it was hard work for everyone both Yolŋu and Balanda, and then it collapsed because some people were not doing the job they were supposed to.

Michael: What should we do tomorrow, maybe talk about how Yolŋu meaning and value gets mapped on to Yolŋu life.

Maratja suggested that the Yolŋu are thinking globally whereas balanda seem to be more linear, systematic, even though they are separate, they are two extremes, they are complementary, and now we can work together we can sit down and talk and come up with some agreements, sometimes we agree, then we talk.

Anthea suggests that we do some school-style maths work tomorrow, just so we remember how it used to be.

Bryce made a link between caring for country and the way in which balanda use of maths may have contributed to global warming. Maybe Yolŋu art with its use of environmental patterns is a way for Yolŋu maths to help us deal with environmental problems.

Maratja returned to the theme of balanda maths and science, and stated that for Yolŋu children to begin to become analytical, and problem solvers for their community, we Yolŋu need to talk over these issues, because our children are caught up in this system, where this educational system is not good. There isn’t any value inside there for our children.

We Yolŋu need to talk about it, and flesh out some of the ideas, and come to agreement, put our heads together, and find some answers for our children. In the past it was good, but nowadays it’s not good enough, we’re not at the cutting edge, we’re not making an impact on the educational system. For some reason these two systems don’t recognise each other, like this old man (Michael) asked. How can the two systems be married? Is it possible for that to happen?

Now we’ll start thinking about that instead of putting it into the too hard basket, it’s time for us start to contribute, and try to make an impact. The end of the day the education system for Yolŋu is failing, it’s failing big time. The wishes and aspirations for Yolŋu autonomy, self management, where’s the meaning for them. What are we doing about it? Where are the educators, the Yolŋu speaking out for what they feel is right and proper for us? We Yolŋu need to challenge the system, speak out strongly for what we believe. Maths is a science. How can we balanda and Yolŋu recognise and join together, and work together, clicking, lock on to each other? Can it happen? The education department has been talking about it for many years, will we just keep talking like this? What are we achieving in this meeting in this workshop?

John said he hoped that we will find it. Once the two systems could speak well to each other, Yolŋu and education and teachers, but I can see a story emerging which is djuŋunymirr (based in Yolŋu law). You have experience and you also have a pathway, and all of us can talk about the base context, and maybe tomorrow the context will emerge, and the nature of context-driven maths, when we listen to you all.

Michael said we are looking for something based in Yolŋu experience, readdressing the questions of maths education in schools, making recommendations as to how it could go on better. What is the real problem? Alienation? Contextualisation? If you talk to the NTDEET they don’t use words like alienation, … you are rethinking the foundations of these questions.

Australian Flag at Parliament House.

Image courtesy of Flagstaffotos

Then Gotha suggested she contribute a short story to the discussion. She continued: I went to Canberra, once, and I saw the Australian flag flying above parliament house. And I thought, what is the foundation of this flag? On what is it standing? Here they are teaching us, and our children, teachings without foundations, (luku-warwaryun) it’s looking for a home, for place. They haven’t established a foundation for the children. Where is their place? a purpose for their learning? learning with whom, from whom? The teachings/curricula are coming from Canberra, there is no foundation (djalkiri) for us there. It has come from somewhere else, disrespectfully cutting across (guwal-budapthunaŋur). And if they don’t do something, then Yolŋu will tell them and establish the foundations by themselves so that it can sprout (dhamatjun, bitpitthun) anew in a true and meaningful direction. They are causing us to falter, and lose direction (warwarmaram) for our feet. We are going through without water (ranhdhakkurr), we are not teaching the children well. I was just thinking about that Canberra flag. Where is its foundation? That’s why we’re wandering around without footprints or foundations, Yolŋu and balanda.

Maratja's story

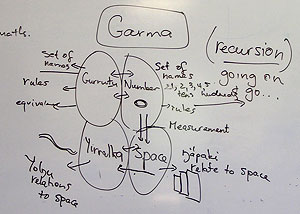

Then Maratja told a similar Canberra story. I was flying from Canberra to Sydney and I looked out of the plane and I saw paddocks, and a river, water flowing and areas, farm land, paddocks, together like that (he draws a picture on the whiteboard of rectangular paddocks adjacent to a winding river), ‘conformity and nonconformity’. That one thing came to me, this (the river) is free and flowing, and these (the paddocks) are…

And Waymamba fills in: ‘traps’

Maratja: And the education system is flowing, like this (pointing to the river).

Then Rose spoke up. I’ll say something short, this is the problem, our experience is different, we go and approach the clever balanda, and we sit with them and share our cultural stories, for their cross cultural experience. We sit with them and teach them every week about Yolŋu culture, and how we live according to Yolŋu traditions. A bad aspect of this, I talk straight. They say. It sounds all right, but maybe that’s okay sometime, those both ways collaborations, some time, but at the moment I’m busy. That’s what the Yolŋu find to be very difficult. We ask for the opportunity to teach those balanda, about what we find in our communities. We, all of us here went to school properly, but now we find schooling very difficult because we don’t see things happening both-ways, our experience was making arts and crafts, looking back, during those school years we learnt ceremony and song, we learnt English and Yolŋu language, then we went hunting and we learnt the names of the various shellfish. Now it’s different, we only hear the Balanda ideas now. I think it’s because the old people are not going into the school and helping and supporting, sitting with us. Sorry but I’m talking about those dead people (who used to be welcome in the school program). One day I was talking to this person who said. You should be an anthropologist yourself. We, these people here sit with balanda and communicate, but the young people cannot do this. We learnt together, finding funding (for Yolŋu elders to participate in education). Does this mean anything today in the community? Yolŋu old people still hold sacred ceremonies and the parents are not preparing the kids for them, to listen properly. Balanda and Yolŋu need to sit together and learn from each other. Our success comes from giving each other understanding, that’s how we will succeed.

Gotha used another metaphor to talk about how Yolngu see their futures in terms of the balance with balanda education. We are looking forward for a new sign, the evening star is setting, there’s another sign coming, if we accept it, which way will we decide to go, to the west or the east? The evening star, or the morning star?

We broke for the evening, discussing arrangements for dinner and coming together the next day.

----------------------------------

On Sunday morning Michael and John both started with a bit of a summary of what we thought we had achieved the day before.

Maratja was the first to make comment. The expectation from the balanda teaching the Yolŋu students is that Yolŋu kids will arrive at school knowing the maths, but it’s not the case. Some of us Yolŋu, we have survived through the mission era, coming from a mission school. Think of the techniques or style the missionaries used, much repetition and talking to the kids’ families. They would give the reason why you need to learn the background, the homework, then we started to comprehend some of the mathematical maths mind in the balanda maths. We started to hold on to the little bit we know, but there wasn’t any groundwork. The groundwork was not prepared, the connections to contextualise hasn’t been done sufficiently. The leaders of our community now come from that mission time. If we get education and know a little bit of maths, they just think about sums, that mindset is there from the mission time. So we need to start to tease out a bit more, flesh it out, and then we can get some understanding about how the Yolŋu understanding starts to come in. This is where some of the bilingual starts to be operating. I might be going in circles here but this is something that we have to talk about with more Yolŋu, needs to be taken a bit further, to get that clarity, even ourselves.

Maratja went on to refer to the metaphor of ganguri, a yam found in the vine thickets. You start by finding the leaf of the ganguri, which is a good thing to find. Then you trace it carefully back to the root. If at any moment the stem breaks off, you will lose sight of the connection back to the food source.

Then Anthea spoke up. Can I respond with what I thought a lot about yesterday? I used to be a balanda maths teacher, a lot of issues you are struggling with are not just your problem, they are a problem all over the world, maths teachers everywhere are struggle with this question. About how to get children in school to take an interest in this thing called mathematics, because even though it’s easier for balanda kids because they’re listening in English, they’re still dealing with something which is basically a foreign idea which is dividing up the world into numbers. That process has happened in Europe and America, and has come across the world. Well it didn’t actually start in Europe it started in the middle east, this business about thinking the world in numbers. It has become so common, that we have forgotten about its history, have forgotten that it’s actually not natural, and I sometimes think as a maths teacher, that I want to remind kids, that maths is almost like a game you play with the world, it’s a fairly useful one but also a dangerous one. We’ve been talking a lot about how we get to understanding through metaphors, well here’s a metaphor: a hammer. A hammer is a tool but if it’s the only tool you’ve got, you walk around the world looking for nails or things to smash. And some people live a bit like that, if they only have numbers in their head, that’s their only tool for dealing with the world. They go around looking for things to do with numbers, maybe they are accountants and they only think about the world in numbers, or they sit in offices and add up, and think they understand Raminginiŋ because they know how many people there are how many men and women, children and dogs. See, they are reducing the world to numbers because it’s their only tool.

Maratja said ‘statistics’.

Anthea went on. I think that in our classrooms if we were more explicit with children, that it’s a very useful tool, just like hammers can be very useful, as long as you only use them in the right place, and the wonderful thing for Yolŋu children is that they already have this other fabulous map of the world, numbers are like a map of the world, so they get these two powerful maps of the world, that is the issues that even balanda teachers are struggling with out in high schools in other parts of Australia, how to make maths more interesting to kids but also to make them aware that it’s just a tool. It’s not reality it’s not the whole picture of the world. Just a thought I kept having yesterday.

Frank asked. How do people find a pathway? If you go into the jungle or the mangroves, you know how to get back. If you get disorientated, you’re lost. The orientation was fine when it started, and somewhere it stopped. That’s why they can’t get it, they don’t understand the Yolŋu matha over at the school there. When we went to school we learnt English and Yolŋu matha, these days at school they don’t speak in Yolŋu matha (language). I’m just trying to find a pathway. Do you understand what I’m trying to do? I’m trying to find a way of getting in, so that we can also find a way out. Because somehow we go in with this maths and we get disoriented and can’t come out. We get stuck. That’s what possibly happens. I’m trying to tell a story to encircle the problem, to find a way, or a solution about what we’re talking about. What is the best path for what we are talking about? Who is wrong? The teachers? Or the Yolŋu teachers? Or the actual students for not going to school? Where is it that it’s gone wrong? It worked once upon a time when I went to school, and I learnt Yolŋu language and then I learnt English. And as I said yesterday, when I left school I learnt more than when I was at school. And I’m still learning because the school opened up a new world. And I was looking at a different world, as if through binoculars, looking off into the distance.

Gapany thought part of the problem was that they’ve been changing the teachers, every term a different teacher. But back then teachers would stay for the whole year.

Maratja: ‘a high turnover of staff’.

Gapany went on. There would be one maths teacher standing, one literacy teacher, one sports teacher. Not changing all the time, and they would know the children, where they weren’t learning, where they were learning. Where they would be patching up, where they should be building on. That’s how we knew it, but now it’s just changing, changing, changing.”

Then Waymamba said. All of us sitting here have a background in teaching, Michael John, Kathy, I don’t know about what’s in Christian’s background work, Anthea’s a teacher, and all of us teachers, this is what Bulanydjan Anthea said: When kids go into school, they learn differently, this is what she was saying in English, “dividing the world into numbers”, that’s what she said. And I was sitting here thinking ‘That’s quite right, it’s true, our world has its own numbers, different numbers, different ideas, different knowledge, and when the kid jumps over on to the school side, s/he will learn differently, something different’. So over there, the world is dividing into numbers, and the ones over here don’t recognise it, the kids, so that’s a point that we need to look at later on. That’s her point, is there something wrong with that?

Then there was some general discussion, talking about history, where did balanda maths start? With whom? Is it something about the French or something, when it became abstract? Dividing up into numbers, where did it start?

John reminded people of Maratja’s story of the fences and yards (referring back to Maratja’s picture of paddocks on the whiteboard from yesterday), measuring using feet.

Kathy pointed out that because people’s feet were different sizes, they standardized the measurement.

John suggested that maybe they used the king’s foot?

Kathy suggested it was a gold bar.

Anthea pointed out that measurement like this can be useful and dangerous. Once you have a standard measurement you can take it away, go back, go out, measure another country and take the measurement and pretend you own it. If you’re using your own foot you have to be there. That dangerous aspect of maths makes it powerful.

Maratja: So we could identify with the foot and things like that, that’s something that can hit home with the Yolŋu understanding, because that’s pretty much down to earth, if that grounding would be there, and we could start to feel it, the abstract, how can we change the abstract into…

Anthea: … back into something practical,

Maratja: … yes something practical, where’s the reversal in it? You know, get around it sort of thing, so we can get the whole meaning, sort of thing.

Kathy said that early childhood teachers in schools try to do that, teaching with feet, hands, string, that’s what we’re looking at in our project (an ARC project), something doesn’t quite translate, I think its not the kids, it’s the way we try to give the message is the problem, Yolŋu kids are clever, they understand gurrutu they can understand it, I can only do it through people I know, if it’s on paper its…

Maratja: something in the transition will happen, not in the earlier childhood, but it’s in the …, maybe …,

Kathy: where you go from concrete to more abstract, and kids don’t know what they’re missing, but it’s the way we’re teaching it, that’s what I think.

Frank: That’s a very important story I just heard from Kathy, when the Yolŋu kids are learning, they are very, very quick, I agree with that, that’s why I commented in so quickly, because Yolŋu kids are very, very quick, they are very, very intelligent. So we shouldn’t get the kids wrong. Sometimes we blame the kids, it could be something we are doing. We are, what’s the word? - passing on the message, and we are saying something, and they don’t understand it (dharaŋul), could be not their fault, what’s the way we teach, Michael, what’s that word I’m looking for?

Michael: Curriculum? Teaching? Delivery?

Frank: Delivery, and that’s the good point I heard, because Yolŋu children are not stupid. Sometimes we adults think that a kid is stupid but he might know more than me, so don’t blame them, because we can make wrong judgements. That’s a good point I heard from her there, (dharuk gulkmaraŋal) the way we deliver the words or the message, so that we can think here are Yolŋu kids growing up, like yesterday the story about homeland kids whose heads are fixed on in the right place, and when they are taught, they learn, but in our big schools (Milingimbi and Elcho) there are many attractions and other things.

Maratja: I was thinking about this word abstract, the opposite side of abstract is concrete, is that right?

Kathy: Yes, things you can do and see in front of your eyes.

Maratja: So what did you say about early childhood?

Kathy: Early childhood teachers try to do that (concrete teaching), all they do in early maths is that sort of thing, measuring how long a room is or how wide it is with our feet, and then later on we say, guess what! In the ŋapaki world we use this thing called metres, and centimetres so you actually start with what the kids know. You must have seen that a hundred times when you go into school, we lie the kids down, do shapes,

Maratja: So that approach, what is that approach, is that abstract?

Kathy: No it’s really concrete, early childhood, you know, like when you use materials, like rocks etc blocks it might be anything to number, don’t expect them to be able to mentally get the idea first. So most Yolŋu kids up to year 3 go okay in their maths and numeracy, they’re okay because they can see the things and they can do the things. When they get up to about year 5 which is where in the Balanda world that concrete world real things disappear, you might have a calculator that’s about it, everything else should be going on in your head. That’s where lots of Yolŋu and about 8 in 10 white kids lose it. I agree with Anthea, I was thinking that last night, you’re looking at one. Kathy went on to tell of her own experience at school. My teachers didn’t show me what was under those numbers.

Maratja: we need to find the continuation from that process, to delivering maths, that abstract and concrete, continuing all along right up to high school, for Yolŋu whatever, secondary, we need to do that, coupled with other things like Yolŋu contextualisation, using metaphors, parallelisms, similes, things like that, so that people can be absolute in what they are on about.

Kathy went on to talk about how hard it was for her learning maths at school – and she came from a privileged English speaking background. How much harder it is for Yolŋu kids who don’t grow up speaking English.

Frank: And I thought we were the only ones…

Maratja: It’s an alien maths, alien…

Kathy went on to talk about teacher training, some people are good at maths but not at teaching. Even maths teachers have a hard time teaching maths.

Maratja: Maybe we should discuss this with John since he was a maths teacher.

Gapany: Yes he should stand up to speak.

Laughter…

John: Well, think about people in the clinic, the ways health workers use numbers, and at MAF, like (person’s name), and mechanics, Learning in the workplace like (name) was first working in the bank agency, (he mentions other people), looking after it properly, how did they learn all their maths? at school? There were Yolŋu working in the council office back then, and a pilot?

Gapany: They learnt when they were kids.

John: How did they learn?

Gapany: They learnt by going to school and listening to their balanda teachers.

Maratja: By raypirri law was it? By discipline? They learnt because they were trying (birrka’yun) very hard.

Frank: Bulany (speaking to John using his subsection name), I know how to fly a plane, I already took off.

Nyuŋunyuŋu: (Frank’s wife): I wouldn’t get in (to a plane that Frank was flying)

Laughter…

Frank: And I landed it.

Waymamba: When?

Frank: What was the date? It was with the Gove flying club, we had DEET funding, it’s true, because they thought we Yolŋu people didn’t know, but when it comes to a little plane… this computer here (pointing to his own computer), I’ve crashed it a million times, don’t ask me why. But as you say there used to be many Yolŋu who were bookkeepers, all different sorts of jobs.

John: Before, Yolŋu worked in the post office, accountant, book keeper…

Maratja: The family budget…

Anthea: keeping control over your own money too, understanding you own bank statements so that you’re not wasting, losing money, getting exploited by other scams.

Then the conversation turned to money and budgeting…

Frank: Going back to the value of money, we still don’t understand the value of money, that’s why the money goes into your account and then out the next moment like a bucket with holes in it, but we have to understand that.

John: The name of those holes is gurrutu (kinfolk).

Frank: Yes those holes are called gurrutu. The white man might see it and say ‘Ah there’s a hole in the bucket’, but our buckets, the hole is gurrutu, you see, instead of wasting, it’s going back to the family. I don’t know, we Yolŋu look at it from a different angle, “Oh money wasted, oh, ten dollars,” balanda think in a different way, (Liya-different-thirr ŋapaki) Give money for Yolŋu, yes that’s good, (money) for my maralkur, my gurruŋ, mari, waku, (kin terms) or miyalk (wife). Just giving money to all our kin so as not to give cause for embarassment and humiliation.

Maratja: Traditional law (rom) tells us to do that.

Frank: But that was a good point of Anthea’s

Anthea: But it’s not a choice between maths or gurrutu. If you learn to manage your finances there will be more money for your family, not for selfishness but to manage to understand what’s happening to your bank fees, do positive things with it.

Waymamba: Are you saying Anthea that we don’t save money because we don’t know how to? We don’t know how to do it. Or rather I don’t know how to do it. What does it mean not to know how to save?

Michael: Yolŋu always giving, dhapinya, dhapinya.

Waymamba: Yes, give, give, give, give, give there’s nothing left for me, my family when I get paid they’re just lining up for money.

Maratja: Our law says, we have our own ways, have to do the right thing, we’re trying to fulfil our responsibilities, the ancestral laws say tell us from the foundations, (lukuŋur), we mustn’t leave others out, we are instructed (raypirri, ŋarra’ŋur) in ceremonies, not to ignore our relatives, we will be embarrassed to look at them (lay-gori), our law tells us (rom ga barraŋga’yun), we are restoring our kinship, value in kinship, laws, respect, all these more important cultural practice, more important than the money issue, than adding up the world, more so that, that’s why, there’s a question mark there, what shall become of Yolŋu, later, further down the track, all those value studies, really good. Could money, rrupiya go down the drain, or start to accumulate, or start to have another value, for balanda, that’s really my question.

Anthea: So do you think that there’s been some sort of rejection of maths because it’s seen as contrary to Yolŋu values?

Maratja: Maybe, there’s something there…

Anthea: Because that may be a wise response,.

Then followed general discussion which couldn’t be picked up on the audio recording.

Maratja: Well the other side of the coin is, do they really criticise the community by not giving the people responsibility, it’s dependency, always, you know, what can I give? If I give a relative a fish, … that person will be dependent (lay-burakin) on me, so that I can feed him forever. Maybe he can go for fish” for himself, I can teach him so he go for fish himself. Maybe I can teach, “Come on let’s go hunting, go that way, and he’ll catch a fish, so he can feel well, a different approach. But still there’s kinship, it’s very hard, when somebody passes away, then the Yolŋu will be thinking of gifts they have given (wetj), that becomes the forefront, how well you looked after that person.

After further talk, Gurraŋgurraŋ brought discussion back to schooling. The story is it’s going good at Gawa school with maths and English in extra time. I teach them at home explaining to them, then I look at their work and when it gets hard for them I can help them at home, like with rocks, sticks and shells. I use them there at home, and in school we are using blocks to learn and it’s going well, nothing is hard for the kids but it is still simple the work they are doing, just adding, but their understanding is lying there and it’s going well.

After that Kathy brought out the number line which is used as a ‘probe task’ in helping teachers work out how kids are progressing in their classroom maths.

Frank: When I was at school we called it nought, not zero, when we were growing we had pounds and ounces which changed to grams, so all this change we’re getting the wording wrong, that’s what we went through for the last thirty years.

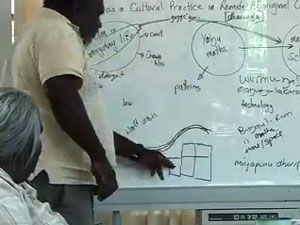

Garma Maths model

Back on Kathy’s assessment test. Doing the assessment test, where does 48 live (on the line between 0 and 100)? Number sense, is he on the right side of the half? We can always check. Kathy talked about one kid counting their way along the line mentally, the teachers haven’t told them about where the numbers live properly, so she stood and counted in her head. Kathy talked about subitising: kids good at this subitising task, part of their visual world, talking about the NTCF ‘maths learning area’ (other areas are science languages, arts, etc, maths is one of them) in my opinion it is a bad document, 3 bits, number sense, spatial sense, measurement – not a good system, we’ve used bits of it at Yirrkala, it’s a map which doesn’t tell you what’s underneath, doesn’t talk about gurrutu and djalkiri which Yolŋu kids bring with them to school as background. Kathy drew the map of garma maths curriculum structure from the Yirrkala school: I think we have worked out how to bring it together and you’ll see the difference – it’s called Garma – four strands, gurrutu, number, djalkiri, space. Kathy talked about the Yirrkala garma maths curriculum, about the proposed 99 year leases and culture clash. We don’t know what’s going on, we live in that world where gurrutu counts and to some extent we live other worlds as well, Yothu Yindi music, bringing together the two worlds of music. Our year 1 kids show not very flash maths results, still something in the division between the two, the Yolŋu part keeps running along but the balanda side keeps starting and stopping.

Dhaŋgal: It’s in those years, that’s when the kids start to stray, that’s why they lose their ability to do it. If you don’t have them sorted by the end of primary school that’s when they stray. We can marry the two… land rights and legislation relating to Yolŋu ways of owning the country.

John: Lets have a break, after the break people might organise themselves and get ready to give a story on tape, for the report, we can talk about how to structure the report, so we can justify the SiMERR money and think about how the website could be structured. Recording short messages, stories and pictures. What languages to use for the reporting?

After the break we recorded people’s final impressions:

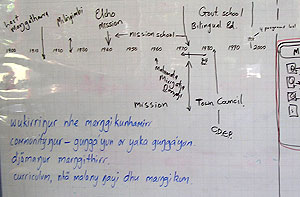

This was Frank’s story: I’m Frank from Milingimbi and my ideas that I was thinking yesterday, one I didn’t bring up, this reminded me talking about money in our lives, from imperial to decimal, big changes, Mabo land rights, it reminded me of a time line which all of us come along, so it’s important our feet have been there. We had a workshop in Alice Springs where we have a time line the development of Aboriginal media, from CAAMA to Imparja, ICTV, SBS ABC, national indigenous tv starting next year, different again, just talking about the time line, the experience we received. We need to understand the gap that came. I can see it from the 60s from the 50s when I started school, left in 67. How long is the average schooling? 12 years? I was the oldest person to leave that year.

Franks Timeline

I left and went to Darwin, that year turning 16, I went to school in Darwin, because no higher schooling was available at Galiwin’ku, then I was learning on the job, radio work, office work, meetings, observing, getting involved in Yolngu language education, making the film about kinship, one of the best things I’ve done. I was looking at the pictures on film, cutting them up, answering the film maker’s questions, yes, no, talking to each other, working together, my ideas went in to help, and then my interests took me in a different direction into media communication talking to people all over the world, two way radio, these are my ideas. (You guys aren’t listening to me but I’m saying it before I forget, I’ve got a bad memory.)

So I was born and raised at Galiwin’ku, I went to school 1954 left 1967 became baker 1969 went to Perth with the school choir for a month my first tour outside of NT after that did other work through school, mainly with Yolŋu matha, gurrutu film making with south Australian film company, 1980s Yolŋu matha kinship movie working with Milingimbi people two former principals Don Williams and Allan Fidock from Milingimbi. During the time I was living and learning I learnt slowly, especially for maths, but after a number of years I caught up with maths, but still I find the maths hard, but I worked out how to add up and take away, and do maths work without using the calculator. So I know those two things, but I mostly like living and helping people who have one idea working out how to make ways forward. There are many ways for me to help them, and I hope they used what I had to share. And at this workshop I expected it to be very hard, but now I think we have been looking for pathways into that hard work, through working with these people who are telling who we are I have found it good, through working with these and I thank John and Bryce and Michael for bringing the group of people together because we have found a way of understanding each other, or a pretty similar position, for ourselves and for our families, kids going to school and the benefit will go to others, that’s my short story explaining, it’s a different sort of story this time, the background to what I’m interested in, how I’ve helped. At the moment I’m acting chairman for the Milingimbi council, responsible to the council how the CEO, a balanda works, and make sure that all the proceedings the papers, documents are all signed, normal administrative work. That’s my work.

Maratja: My name’s Maratja Alan Dhamarrandji I come from Elcho Island. I’ve been living in Galiwin’ku for long time. I’m fifty years old now, getting old and I’d just like to briefly talk about myself. My education was with the mission school and since the government took over, I went to Kormilda College for five years, went to high school, Darwin High School, from there I went to do some apprenticeship training as a fitter with Hastings Deering, with them for about 8 months, went with a motor mechanics course, went down to Alice Springs, did first year, second year, then I failed in electricity. There was maths involved, I failed that and decided not to go back to it again. He wanted me to go back as a motor mechanic. After that I went back to Galiwin’ku and did some other jobs, like community development with the homelands resource centre, bookkeeping. Back to Galiwin’ku to do community work with Marthakal, then from there I went to the council office, assistant bookkeeper, and 1987 I was asked to do translation work and so I learnt about translation principles, did some courses in Darwin at the Summer Institute of Lingistics, and training there, now I’ve got a Certificate in translation from SIL, Certificate 2 in translation. It’s a good job for me. I’ve been there since 1987. I do mainly bible translation work, and I also gained a NAATI national accreditation course. Translator-interpreting work with the course with the health centre or the hospital, and since then I’ve been mainly doing interpreting work. I do radio work also with ARDS with Richard Trudgen, you guys know him, he’s the author of Why Warriors Lie Down and Die. I do a lot of work with him helping with cultural awareness training. I partner with him to do that work.

It’s my open ambition that one day I myself and some other Yolŋu will want to do that kind of work ourselves and Yolŋu can be more proactive in that kind of work, community cultural awareness. Teach balanda maybe Yolŋu too how to become encouraged and ready to speak out for what they truly believe and become more assertive in enforcing what they think is the best of the world out there to know about Yolŋu, and Yolŋu generally understand things, the Yolŋu world view.

One of the things that has come up in this workshop, the maths workshop at CDU run by school of SAIKS CDU with these lecturers here, it’s a sort of a workshop that has really helped me a lot personally to understand some issues, because I do get involved with some of the Yolŋu back in the community. Sometimes they ask me to go to the school. They ask me to do some translation work and help to understand some of the ideas and concepts that need translation and teasing out, to understand some ideas people from the community and school council, and the teacher linguists. Mally McClelland and others, they always ask me to go down and have a bit of a talk about how to make the bilingual school and the Yolŋu maths there to improve, and to have an impact on the Yolŋu and teachers and the kids.

This course here has really broadened my understanding. To think you know some things that is a bit hazy, not really understanding some of the points, issues. And I’d just like to talk about the curriculum - what is it? It’s related to how to teach in the schools, to maths, and to the maths understanding we were talking about. Some of the staff here have been talking about dividing the world into what people think, spaces. Like dividing the world into numbers, some of these staff have been talking about that, and as Yolŋu we need to know how balanda maths and Yolŋu maths can recognise (dharaŋanmirr) and understand each other. Therefore the rom, the curriculum needs to be challenged. We’ve heard what they’ve done over at Yirrkala. It is a good step for Yolŋu maths in general, and seems to be working. We need to really maintain and see that happen really ongoing and full, and support that something good.

I can use this story about ganguri, a ganguri metaphor collecting and findings yams. Like the ladies when they go out for hunting, when they go into the bush some very prickly shrubs can really cut you and cause you harm. It is like that, it was like that. We were endeavouring to find some answers, some solutions, and when you find ganguri it’s hard work, and you go down and find the leaves and the vines and identify it, that it’s the right vine. Then you have to dig it, it’s hard work also to get it out of the soil and it’s a bit like that trying to identify, go through the process. It hasn’t been easy particularly for myself, because most of the people here have been with the teaching profession for long, and they know some of the ups and downs and even some of the blockages, stumbling blocks, pitfalls happening in their profession when it comes to Yolŋu development progress in teaching, the education field.

So coming from Yolŋu, I think for the curriculum we Yolŋu, just like the parents, the community people, we need to have some understanding of what is the rom, the pathway, (dhukarr). How they follow the curriculum, what to teach. We Yolŋu people need to have some basic understanding, so we can, so we are knowledgeable about the curriculum, then we will be able to have a sense of responsibility, the responsibility gets back to us, and that sort of helps us, so we have some thing to work with, to make some changes in the whole of the education system for Yolŋu particularly, because we want to see our kids attaining, getting the best education, and getting good marks, results. That’s what we’d like to see at the end of the day. It’s really important, and I for one, and there are others who would like to see that happen and make our education become real for our people, and make it, when I say real, it has to be meaningful. How does it connect with this workshop? We’ve been talking about the connection, how does it correlate to our understanding of the world view? that’s what’s been said. That’s something that we need to help our people, so that it’s contextualising, using context. We would like to see that happen.This maths problem is not only a Yolŋu problem, but it’s happening in the balanda world as well, that’s a bit of a relief. For Yolŋu we have an opportunity now. We have to make the best education, and good maths education for Yolŋu. We have our Yolŋu understanding of things, how we can build in, marry the ideas and concepts, balanda and Yolŋu ideas coming together and trying to make sense out of it, grounding, even now helping Yolŋu further down the track if they want to get into other areas like specialised maths, high school or maybe university. It has to happen at the community level and the more people that know about it the better, so that we can speak with one voice, solidarity, what is straight (dhunupa) what is true and what is something that we can achieve, and we need to speak out about that idea. Voice our opinion for people in the education field, especially for maths. So it has been a learning process for me, and for all of us here, so I just want to say thankyou for all your staff members, in the Indigenous school here, very good, thankyou.

Maratja was looking at a pot plant in the seminar room. This pot plant won’t grow long in this pot, it has some restrictions, it won’t grow into a beautiful tree, and bear, but if it’s taken out and planted into a good natural environment, it will grow with all the nutrients and other good things from the ground. It will grow into something good. What it’s supposed and meant to be. So I’m comparing it with this garma maths curriculum. My next question is, is this garma maths in the curriculum, finished?

Kathy: It’s the Yirrkala maths curriculum,

Maratja: Only at Yirrkala?

Kathy: Yes only at Yirrikala.

Maratja: Why isn’t it at other communities like Galiwin’ku and elsewhere

Kathy: Well because they think it’s up to Yolŋu…

Maratja: Up to Yolŋu? because some people don’t know about this. The law inside (garma maths), it will stop it, it’s a stumbling block. So that, there’s been at Yirrkala, there were some graduates? How many graduates (from secondary)? Empowering Yolŋu to speak out. What they believe is right (dhunupa), we want quality, not just quantity, there are people coming out from the school and they haven’t learnt properly, particularly maths things, because there is high expectation in the community. We want the kids to go to the office, bookkeeping, be accountants, and do all maths related work, even doctor work. We want Yolŋu people qualified, and there are too many balanda. People are saying there are too many balanda roaming around doing plumbing work. Where’s the Yolŋu? And the balanda say, ‘Where’s your kid? They’re not going to school, they need to be trained to do this work’ that’s what they’re saying. Real life issues, so there’s a demand and a push for education that this should be happening.

Dhaŋgal’s brother Djalu playing Yidaki

Then it was Dhaŋgal’s turn to make her summary. My history is that I used to hate maths, in school, I wasn’t interested in maths. Later on after school, what I learnt in school was useful to me in later years through my work. That’s when I realised I was using maths in areas like first as a clerical assistant in an office, and at that time they had a radio weather centre in Darwin, they collected weather reports from all the communities, (reporting on the weather through numbers). I began to realise that I was looking at the clouds and putting them into numbers on to paper and transmitting the numbers to Darwin. Then also I worked in the bank clerk position, and I learnt about all the money, numbers. After that I stopped, and started to help my brother with the yidaki (didgeridoo) business, and there are maths involved in the yidaki.

I’ll tell you the Yidaki story. Maths of the ways in which the sound goes. In a place Warrk in Caledon bay area, the Marrakulu and Galpu lived there, who will make the west wind blow. The Marrakulu played the Yidaki and waited for the wind to blow around towards Warrk, but nothing. Then the Galpu, the noise of the Yidaki went down with the wind, and the sound went down Gumumuk and over at the escarpment, hits Gumumuk and went down to Golbin, goes down, turns around that wind, as the west wind, blowing, it comes back over there at Warrk where the gayku is standing, hit it, it took the wind, and the sound came out vibrating as “dethuŋ”, we can hear it. So that’s the story, and the maths inside there is called measurement, weight, length and width, and the sound on that side they have machines to measure that. And the body of a yidaki can be measured in weight, depth, length, and baywarra, the wititj snake, and one short yidaki is the wind one, barra, heavy, and the other is relatively light.

Frank added: It’s not a particularly high pitch that yidaki, high fidelity, it’s mid range. But sometimes we play to a certain note, in the middle of the keyboard, I’m talking as a musician now, in the middle of the bass clef and the treble clef is the C. Go on off you go!

Gurraŋgurraŋ gave her summary. The work we’re doing with the children, like one thing we’re learning about is distance, like how many it takes from Galiwin’ku to Gawa. Also I found a challenge when Colin gave me the responsibility for the generator, and how many litres to pour into the generator and how many there are in the tank, how I need to divide it up, that’s my personal experience, I learnt that and then I was explaining it to the children, just myself as the Yolŋu (teacher).

Gothe explains about turtle tracksdrawing

Gotha then told her story, after Laynbalaynba had drawn turtle tracks and nesting sites on the white board. (insert picture). You can see these turtle tracks, she’s coming out of the water and she made this, and here, and here and here, and here, and back down. So if a Yolŋu who knows, he’ll see what lies there, there’s a secret that he will see in these tracks. This is what he is searching for, and he will prod and find out where the turtle eggs are, and if he doesn’t know what he’s doing; when you look on the Naŋinyburra beach, he will dig until he has no energy, he’ll prod there, and get tired, he’ll poke here, until he gets tired, and here and find nothing.