Yolŋu Aboriginal Consultants Initiative

Projects

Yolŋu Longgrassers on Larrakia Land

An investigation into issues affecting Yolŋu people living under the stars in the Darwin area. Download pdf

Healthy Heart and Lungs

About the project

Miscommunication between English speaking health professionals and non-English speaking Aboriginal patients is serious and well-documented problem in Northern Australia.

Yolŋu consultants were originally involved in an extensive research

project entitled Sharing the True Stories: Improving Communication

in Indigenous Health Care. See www.cdu.edu.au/centres/stts/home.html ![]()

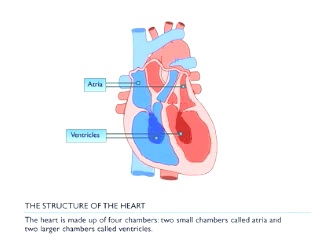

In the Healthy Breathing and Heart project, we have been working on examining, evaluating and producing multimedia objects which can enhance the building of shared understandings between Aboriginal patients and English-speaking health professionals.

Stage 1 involved a workshop bringing together Yolŋu consultants and a Respiratory specialist to examine and evaluate a range of multimedia and to make recommendations for further development.

Stage 2 involved the collaborative production of a multimedia resource to be used in patient education, in the training of health workers and interpreters, and for general educational use in schools and health clinics.

The project partners were

This project was supported by the Australian Government's Department of Health and Ageing

What we did

Michael opened by talking briefly

about the Yolŋu consultancy initiative and the agenda for the two

days. Prof Pierce had prepared four powerpoint presentations which

included multimedia objects for discussion. Over the two days,

we had time to look at the first three presentations: breathing

structure and function, gas exchange and circulation, and diseases

processes. We didn’t have time to look at the fourth presentation

on treatment.

Michael opened by talking briefly

about the Yolŋu consultancy initiative and the agenda for the two

days. Prof Pierce had prepared four powerpoint presentations which

included multimedia objects for discussion. Over the two days,

we had time to look at the first three presentations: breathing

structure and function, gas exchange and circulation, and diseases

processes. We didn’t have time to look at the fourth presentation

on treatment.

During the presentations we stopped frequently to discuss the multimedia and a range of issues to do with Yolŋu perceptions of the body, Yolŋu understandings of the biomedical model, pathology and treatment, interpreting and interpreter training.

Christian videoed the workshop,

and Michael and John made some notes on computer. Over the next

few weeks, Christian, Michael and John will look carefully at the

videos and develop a draft of a detailed report for Rob and the

Yolŋu consultants to work on. The full report will include an outline

of a recommended multimedia development process which emerged from

the workshop.

Christian videoed the workshop,

and Michael and John made some notes on computer. Over the next

few weeks, Christian, Michael and John will look carefully at the

videos and develop a draft of a detailed report for Rob and the

Yolŋu consultants to work on. The full report will include an outline

of a recommended multimedia development process which emerged from

the workshop.

Stage 1: Key Findings

It

is currently very unusual for interpreters to use multimedia or

other graphic material in health interpreting. The interpreters

also felt that they needed more training for health interpreting

so they can better understand the structures and processes they

need to communicate. There are contexts where multimedia could

be used which are outside of interpreting work – eg as DVDs handed

out to homes with DVD players, in health clinic waiting rooms,

in schools etc.

It

is currently very unusual for interpreters to use multimedia or

other graphic material in health interpreting. The interpreters

also felt that they needed more training for health interpreting

so they can better understand the structures and processes they

need to communicate. There are contexts where multimedia could

be used which are outside of interpreting work – eg as DVDs handed

out to homes with DVD players, in health clinic waiting rooms,

in schools etc.

ŋir’ is the Yolŋu word for breath, but also has a wider meaning, to do with life force. When Yolŋu feel a pulse in the wrist or neck, they call that ŋir’. This doesn’t mean that they think that it is air that is passing through the arteries, it means they are feeling the life force which is both breathing and circulation together. This discussion opened the discussion on whether the heart and lung stories should be told separately or together. People agreed that the story could be broken up into pieces, but careful work would need to be done to decide where those division should be made.

The

discussion often returned to the question of language. Frank said

that no matter how detailed a Yolŋu language explanation was, it

may not ever properly convey what the English words mean. It was

also agreed that more work should be done talking with elders about

Yolŋu words for different parts of the anatomy, but also that we

need to find ways of talking about healthy breathing and heart

which younger people understand, using their everyday language.

In discussions about the ways of generating a Yolŋu language audiotrack

to accompany a DVD, it was agreed that a conversational approach

with interpreters discussing images using natural language - asking

and answering questions, commenting and agreeing, older and younger

people’s ways of talking – would be the best way to convey meaning

and keep interest levels high. It was suggested that various Yolŋu

languages could be used together which is normal practice in everyday

Yolŋu life.

The

discussion often returned to the question of language. Frank said

that no matter how detailed a Yolŋu language explanation was, it

may not ever properly convey what the English words mean. It was

also agreed that more work should be done talking with elders about

Yolŋu words for different parts of the anatomy, but also that we

need to find ways of talking about healthy breathing and heart

which younger people understand, using their everyday language.

In discussions about the ways of generating a Yolŋu language audiotrack

to accompany a DVD, it was agreed that a conversational approach

with interpreters discussing images using natural language - asking

and answering questions, commenting and agreeing, older and younger

people’s ways of talking – would be the best way to convey meaning

and keep interest levels high. It was suggested that various Yolŋu

languages could be used together which is normal practice in everyday

Yolŋu life.

It was made clear several times that the ways in which a doctor talks to a balanda patient about their bodies, sickness and treatment, is not always appropriate when treating Yolŋu and talking to their families. There are some things that should not be talked about, and other things which should be talked about in particular ways or to particular people or not in front of particular others. This is sometimes to do with women’s business, sometimes to do with kinship restrictions, but there are other reasons as well. That’s another reason why interpreters are very important in Yol\u health, because they understand the rules of communication.

Stage 1: Resources

Transcripts from Interpreting Multimedia (Healthy Lungs and Heart)

Day 1: Session 1 ![]() | Session

2

| Session

2 ![]() | Session

3

| Session

3 ![]() | Session

4

| Session

4 ![]()

Day

2: Session 5 ![]() | Session

6

| Session

6 ![]() | Session

7

| Session

7 ![]() | Session

8

| Session

8 ![]()

The transcripts have been transcribed from video taken during 8 sessions over two days. Powerpoint slides are included in the transcript when they are being discussed.

Stage 2: What we did

Stage

2 began with the identification of a group of bilingual bicultural

interpreters who have had experience in health interpreting. They

were Jane Galathi, Rachel Baker and Helen Guyulun. This group met

together with Anne Lowell and other CDU academic staff who had been

involved with Stage 1 and have worked on communication issues in

cross-cultural medical contexts for many years. The collaborative

analysis began with discussion in Yolŋu languages about key Yolŋu

and biomedical concepts for building shared understandings around

healthy hearts and lungs. This led to extensive work in the evaluation

of existing multimedia resources, and the selection of the most useful

available resources.

Stage

2 began with the identification of a group of bilingual bicultural

interpreters who have had experience in health interpreting. They

were Jane Galathi, Rachel Baker and Helen Guyulun. This group met

together with Anne Lowell and other CDU academic staff who had been

involved with Stage 1 and have worked on communication issues in

cross-cultural medical contexts for many years. The collaborative

analysis began with discussion in Yolŋu languages about key Yolŋu

and biomedical concepts for building shared understandings around

healthy hearts and lungs. This led to extensive work in the evaluation

of existing multimedia resources, and the selection of the most useful

available resources.

Permission for the use of the copyright images and animations was obtained. The resources were integrated into a narrative sequence and a narrative text. The text was produced collaboratively and elaborated the functions of heart and lungs – from a Yolŋu point of view, but working with the biomedical model of the body. A first version of the narrative was recorded, and back translated into English for checking by a medical professional. A multimedia designer integrated the various images and animation into Version 1. A period of intense evaluation followed, with suggestions being incorporated into Version 2. Once the sequence was agreed, a final recording of the audio was prepared in a studio and integrated into the multimedia process. The DVD was finalised, a cover and notes prepared, and 50 copies of the DVD were prepared and sent out to remote clinics, the Aboriginal Interpreter Service, the Batchelor Institute of Indigenous Tertiary Education (where training for interpreters and health workers take place) and a website was set up for ongoing evaluation and further dissemination of the DVD. The researchers are continuing to seek funding for further development of this resource to extend to other parts of the body, and to other languages.

Stage 2 Resources

Download ![]() report

of stage 2

report

of stage 2

Sample of Draft DVD

Stage 2: Future Directions

Having a collaboratively produced DVD resource is only the beginning of the process. We now need to find ways of integrating the resource into the life of Yolŋu communities inside and outside the clinic, and in the major hospitals where Yolŋu are treated.

We need to keep examining how different knowledge practices come together in the context of biomedical health, and how objects like our DVD may play a role in knowledge work. How do Yolŋu interpreters use digital objects? How do health workers use them? How do English-speaking professionals use them? How do the families of medical patients use them when they talk among themselves, making decisions about treatment options? We need to maintain this website, and pay attention to the feedback we receive, and look for opportunities to extend the project to other language groups.

We will work with the Aboriginal Interpreter Service to develop a plan for customising the resource to other key NT languages. We will use the collaborative methodology to investigate the development of similar resources or other parts of the body. We will make the practices and the advantages of the transdisciplinary research model widely available through the website.

Stage 3: Healthy Breathing and Heart

We now have a digital resource combining an animation of the anatomy and physiology of the heart and lungs, with a voice over in Djambarrpuyŋu. The voiceover was produced by a number of consultants reading a Yolŋu language text which had been translated from an English primary text. (For the original text and back translation into English by Maratja, click here.)

Evaluation:

The draft resource has been carefully evaluated by a group of Yolŋu – including health workers and interpreters, and people with little experience in either health work or interpreting. Anne Lowell and John Greatorex both worked with Yolŋu on the evaluations.

This is a short summary of the main points to emerge:

- Most of the comments were about the voiceover. Sometimes Yolŋu words were used to describe parts or functions of the heart and lung system, but they are not the words or uses of everyday Yolŋu life, so many Yolŋu would not understand. For example, dhukun, which commonly means ‘rubbish’, and is used to denote ‘carbon dioxide’ as opposed to ‘oxygen’, gurrkurr which commonly means ‘sinew’, and is also used to mean ‘artery’ and ‘vein’. Wata, which commonly means ‘wind’, is used for both ‘oxygen’ and ‘carbon dioxide’. Watamirr mayaŋ literally means the ‘neck with air’ is used for trachea, but not properly understood.

- Some English words, not translated, were not understood: ‘ white blood cells’, ‘percentage’, ‘plasma’, ‘litres’. There’s too much talking, and too few images. It goes too quickly and would need to be seen several times.

- A lot of the talking doesn’t really make sense to many Yolŋu: it’s ‘djuŋunymiriw’ – has no message.

- The way voiceover and representations were put together would not be understood by the older or the younger Yolŋu.

- The story needs to be broken into pieces: munguykum. Cutting open a real lung and heart to look at the circulation would help people understand (but of course this is not practicable in a clinical setting). “Let’s do it again so that all those sections interesting to Yolŋu can be better explained”.

Priorities and Focus of further development work

Given that some of the translations and some of the graphics were difficult to understand, and given that we hope to further develop a useful resource to other areas of the body (kidneys etc), there are a few questions which emerge which may help us to prioritise the directions in which we move - What level of detail is necessary for the sorts of education and communication contexts we invisage? and How do we make decisions about where to invest our energies?

- We should think about:

- the burden of disease in the Yolŋu population. Some epidemiological work would help us to identify where the most serious health and medical issues arise in the Yolŋu population and this would help us focus our work.

- the burden of communication, and the possible role of graphic images in decision making – some common diseases (eg COPD) may be less difficult to represent graphically than others (eg diabetes)

- the need for informed consent, and the nature of the knowledge

necessary to produce informed consent. For example, ‘gas exchange’

has turned out to be difficult to demonstrate. It could be argued

that an understanding of gas exchange is important for health education,

but not so important for consent to surgery, and decisions about

the level and detail of microscopy to represent must be informed

by an understanding of the contexts in which the resource will

be used.

Workshop April 2010

We ran a further workshop which to improve the product. In the workshop our approach was to:

- work to collectively evaluate the product further, and record a collaboratively produced voiceover conversation which will be carefully edited to solve some of the problems of language identified in the evaluation. We believe a conversational or dialogic approach to developing a voiceover will solve some of the awkwardness which comes from text translation and script-reading, and will also have the effect of situating the digital object as a participant in the negotiation of shared understandings, rather than as a repository of biomedical truth.

- following the suggestion of some evaluators, we plan to conduct a session dissecting a wallaby and looking at and talking together about its heart and lungs.

- look carefully at the parts of the current animation which work

successfully without a voice-over explanation and use these as

a basis for thinking about how a wider application could be developed

which is entirely language-free – thereby making itself useful

to all language groups, and possibly avoiding the confusing and

unnecessary a priori assumptions about the body embedded in language

and especially in English.

Other questions we need to consider

What about the ethics of the digital object. The medical animations on the website YourPracticeonline.com.au say “this video is for educational purposes only and should not be used for making a decision about surgery”. How do we understand the ethics of these objects in ensuring informed consent?