RIEL news

PhD research on threatened bird finds bird may not exist

New research from a Charles Darwin University ornithologist suggests that an endangered subspecies of bird may not be endangered. In fact, the research suggests that the subspecies may not exist at all.

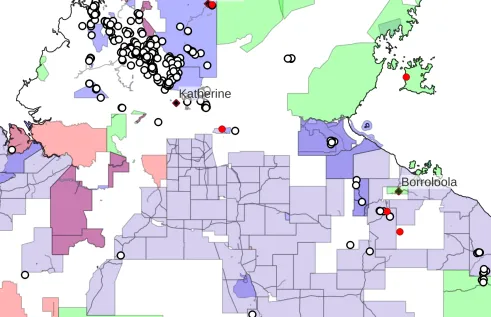

Dr Robin Leppitt recently completed a PhD with the Research Institute for the Environment and Livelihoods on the Alligator Rivers Yellow Chat, an endangered subspecies of Yellow Chat that lives largely in Kakadu National Park. Using genetic analysis, Dr Leppitt found that the DNA of the Alligator Rivers subspecies is not distinguishable from the DNA of its nearest relative, the Inland Yellow Chat, which suggests that it may not be a unique subspecies.

“I don’t think many PhD students have managed to find some pretty compelling evidence that their study species does not exist. To be honest, I have pretty mixed feelings about it.” Said Dr Leppitt.

“In a nutshell, our results suggest that the Alligator Rivers Yellow Chat is not deserving of subspecies status and that it is likely just a northern population of the Inland Yellow Chat, which is not classified as endangered.”

Dr Leppitt studied the Alligator Rivers Yellow Chat for 5 years, trying to learn more about why it was so rare.

“The Alligator Rivers Yellow Chat lives almost exclusively on floodplains, and we believe those floodplains are threatened by inappropriate fire regimes, feral pigs, and invasive weeds.” Said Dr Leppitt.

It was while investigating the ecology of the Alligator Rivers Yellow Chat that Dr Leppitt learned that there were some doubts about their taxonomy, so decided to compare the DNA of the different subspecies of Yellow Chat. The challenge was that for a DNA comparison, he would need some tissue from each of the three subspecies, something from which he could obtain DNA.

“Given the Alligator Rivers Yellow Chat is so rare and can be quite hard to find, we were initially worried about obtaining samples to pull DNA from. Luckily, with some help from some very experienced bird banders, we managed to capture 21 Alligator Rivers Yellow Chats and 11 Inland Yellow Chats.” Said Dr Leppitt.

“We capture them using mist-nets, then sample a few of their chest and belly feathers that fall out naturally during capture.”

Dr Leppitt then spent several months in the lab, extracting and then comparing the DNA of the Yellow Chats he had obtained feathers from. Sure enough, when the results came back, there was no significant difference between the DNA of the Inland Yellow Chats and the Alligator Rivers Yellow Chats.

“If two populations have such similar DNA, and there is minimal if any difference in their appearance, it’s quite likely they are in fact the same, large population, and not two different subspecies” Said Dr Leppitt.

Whilst the result represents compelling evidence that the Alligator Rivers Yellow Chat may not be as unique as once thought, Dr Leppitt says more research is required before an official change to the taxonomy is made.

“Before we combine the Alligator Rivers subspecies with the Inland subspecies, we need to double-check using some more advanced genetic sequencing tools, and also find out more about how the populations move.” Said Dr Leppitt.

“There is still a lot we don’t know about these birds, in particular what the Alligator Rivers population does in the wet season when much of their habitat is flooded. Maybe that is when they are heading south and interacting with the Inland subspecies.”

Despite questioning their taxonomic legitimacy, Dr Leppitt would like to see the Alligator Rivers Yellow Chat be conserved into perpetuity.

“They are a unique and beautiful bird for the Top End, and the majority of the population lives in the world-famous wetlands of Kakadu. Even if this subspecies is no longer legitimate, continuing to protect these birds and their floodplain habitat should benefit the whole ecosystem.” Said Dr Leppitt.

This research was supervised by Prof. Stephen Garnett, Prof. John Woinarski, Dr Peter Kyne, and Dr Luke Einoder (Northern Territory Government Department of Flora and Fauna and Kakadu National Park). The project was supported by Charles Darwin University and the Threatened Species Research Hub of the National Environmental Science Project, Commonwealth Government, Australia.

Related Articles

50 Years of Darwin Wildlife: A New Research-Led Approach

Volunteers have shouldered the burden of shorebird conservation in the Top End for more than half a century, but new research from Charles Darwin University (CDU) suggests it’s time for the government to take responsibility for all of the Northern Territory’s residents – including those with wings.

Read more about 50 Years of Darwin Wildlife: A New Research-Led Approach

CDU strengthens China partnerships to drive sustainable agriculture and aquaculture research

Chinese delegates visited Darwin in August as part of a Charles Darwin University project between Australia and China on tropical aquaculture and cropping.

Read more about CDU strengthens China partnerships to drive sustainable agriculture and aquaculture research

Consideration of First Nations cultural values in mining rehabilitation in the NT

Master by Research student Will Kemp investigated the consideration of First Nations cultural values in mine site rehabilitation planning, finding that the regulation of mining approval needs to achieve clearer agreed goals with respect to First Nations cultural values, that companies must commit to as part of the initial approval process.

Read more about Consideration of First Nations cultural values in mining rehabilitation in the NT